Building Professional Skills That Actually Stick: A Practical Guide to Meaningful Growth

Let’s be real—you’ve probably started learning something new, felt pumped about it for a week, and then… life happened. You got busy, distracted, or the initial excitement wore off. Sound familiar? The good news is that building skills that actually last isn’t about willpower or finding the perfect course. It’s about understanding how your brain works and setting yourself up for real, sustainable growth.

The difference between people who develop genuine expertise and those who collect half-finished courses comes down to a few key principles. And the best part? You can start applying them today, regardless of what skill you’re working on or where you’re starting from.

Why Spaced Repetition Changes Everything

Here’s something neuroscience has known for decades but most learning programs ignore: your brain doesn’t consolidate memories the way you think it does. Cramming information into your head in one session? That information is gone within days. But reviewing the same material at strategic intervals? That sticks around.

Spaced repetition isn’t fancy or complicated. It’s the practice of reviewing information just as you’re about to forget it. So instead of reviewing something once and calling it done, you review it after a day, then a week, then a month. Each time you do, the memory gets stronger and lasts longer.

The real power here is that this method is backed by serious research. Studies in cognitive psychology show spaced repetition can improve retention by 300% compared to massed practice. That’s not a small difference—that’s the difference between actually learning something and just feeling like you did.

When you’re learning a new skill, build spaced repetition into your system from day one. Use flashcard apps, create review schedules, or set calendar reminders. The format doesn’t matter much—consistency does. You’re basically hacking your own memory to work with your brain instead of against it.

Deliberate Practice: The Unglamorous Secret

There’s a concept in skill development called “deliberate practice,” and it’s nothing like what most people think practice is. It’s not putting in hours. It’s not repeating the same thing over and over until it becomes automatic. It’s something much more specific and, honestly, much more exhausting.

Deliberate practice means working on the exact parts of a skill that are hard for you, getting immediate feedback, and adjusting your approach based on that feedback. It’s uncomfortable. It’s slow. And it’s the only thing that actually builds expertise.

Let’s say you’re developing public speaking skills. Deliberate practice isn’t giving the same comfortable presentation to your team every month. It’s recording yourself, watching the recording (cringe-worthy but necessary), identifying exactly where you stumble or lose your audience, and then doing targeted drills on those specific weaknesses. Maybe you struggle with pacing. So you practice just the pacing part, with feedback from someone who knows what good pacing looks like.

This is different from just practicing more. More isn’t the answer. Better, more targeted practice is. The American Psychological Association emphasizes that expertise development requires focused, goal-directed practice rather than passive repetition. The research is clear: hours of unfocused practice doesn’t get you where you want to go. Strategic, uncomfortable practice does.

When you’re building any skill, get honest about what you’re actually bad at. That’s where your practice time should go. Not on the stuff you’re already decent at—that’s comfortable, but it’s not growth.

Building Skills Into Your Daily Life

One of the biggest reasons people don’t stick with skill development is that they treat it like something separate from their actual life. They have “learning time” and “real life,” and real life always wins because, well, that’s where everything else is happening.

The solution is habit stacking—attaching new learning activities to habits you already have. This works because you’re not adding something new to your schedule. You’re piggybacking on something you already do.

Maybe you have coffee every morning. That’s your time for 10 minutes of focused learning on whatever skill you’re developing. Or you’re stuck in traffic during your commute? That’s your spaced repetition window. Already taking a walk? That’s when you listen to educational podcasts or review your notes.

This approach is backed by behavioral psychology. Research on habit formation shows that linking new behaviors to existing routines dramatically increases the likelihood of consistency. You’re not relying on motivation—motivation is unreliable. You’re using the structure you already have.

The key is being specific. Not “I’ll practice more.” That’s too vague. “I’ll spend 15 minutes reviewing flashcards right after my morning coffee, Monday through Friday” is something you can actually do. When you’re thinking about career development and skill growth, these small, consistent actions compound into real expertise over months and years.

Getting Feedback That Actually Helps

Feedback is essential for skill development, but not all feedback is created equal. Some feedback is noise—it’s unhelpful, discouraging, or just wrong. Other feedback is gold. The difference matters.

Good feedback is specific, timely, and actionable. “Good job” is nice but useless. “You’re great at explaining complex ideas, but you rush through your examples—slow down by 20% and let people absorb what you’re saying” is something you can actually work with.

The challenge is that good feedback is hard to get. Your friends might be too nice. Online strangers might be too harsh. This is why finding the right mentor or joining communities around your skill makes such a difference.

When you’re developing skills intentionally, actively seek out feedback from people who are ahead of you. And be specific about what you want feedback on. Don’t ask “How am I doing?” Ask “I’ve been working on my ability to structure presentations—what’s one thing I could improve?” Specific questions get useful answers.

Also—and this is important—feedback is only useful if you actually use it. Getting feedback and ignoring it is just noise. The cycle that matters is: attempt → get feedback → adjust → attempt again. That’s where the learning happens.

Breaking Through Learning Plateaus

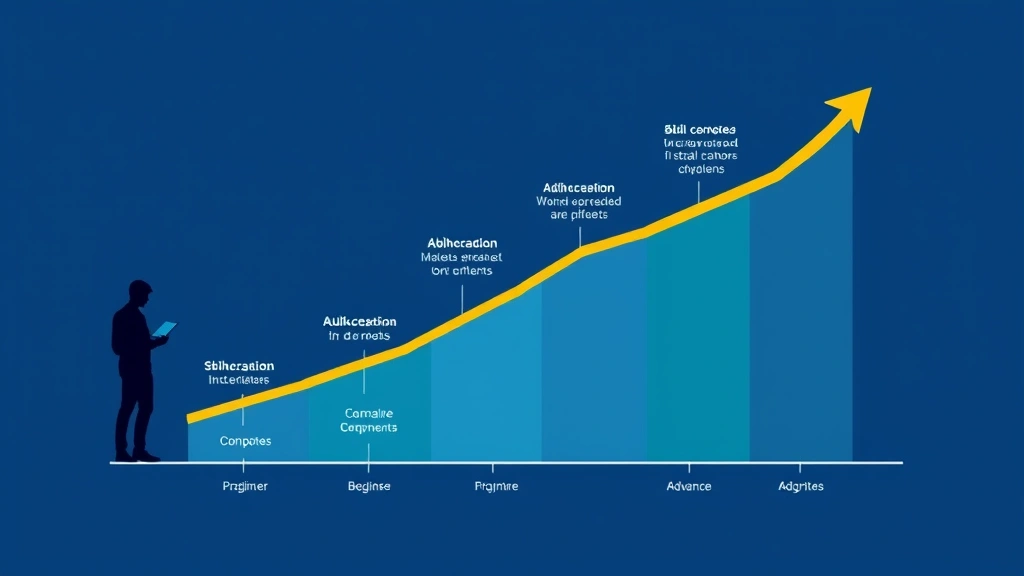

At some point, you’ll hit a wall. You’ll feel like you’re not improving anymore. You’re putting in the work, but nothing’s changing. This is a learning plateau, and it’s completely normal. It’s also temporary if you know how to handle it.

Plateaus happen because you’ve adapted to your current challenge level. Your brain got comfortable. The solution is to increase the difficulty or change your approach. Push yourself to the edge of your ability again. That’s where growth happens.

This might mean taking on harder projects, setting more ambitious goals, or finding a new mentor who can push you further. When you’re focused on continuous improvement, plateaus aren’t failures—they’re signals that you need to level up your challenge.

The research on this is pretty solid. Studies on skill acquisition show that learning progress follows a pattern of rapid improvement followed by plateaus, and breaking through plateaus requires increasing task difficulty. So when you feel stuck, that’s not a sign to give up. It’s a sign to push harder.

Why Community Matters More Than You Think

You can learn a lot on your own, but you won’t stick with it as well. There’s something about community that makes the difference between a skill you’re dabbling with and a skill you’re actually building.

Community does a few things: it provides accountability (you’re less likely to skip practice if other people know you’re working on this), it provides feedback (other people in the community have perspectives you don’t), and it provides motivation (seeing other people progress is genuinely motivating).

When you’re investing in professional development, don’t do it in isolation. Find your people. Join a cohort-based course, find a mastermind group, get an accountability partner, or participate in online communities around your skill. The structure and social element matter way more than you’d think.

The accountability aspect is especially powerful. Research on public commitment shows that stating your goals publicly and being accountable to others significantly increases follow-through rates. It’s not weakness to need this. It’s smart design.

How to Actually Track What You’re Learning

Progress isn’t always obvious, especially in the early stages. This is why tracking matters. Not in an obsessive way—just in a way that lets you see that you’re actually moving forward.

The best metrics are specific and measurable. If you’re developing communication skills, “I’m better at presentations” is too vague. “I can deliver a 30-minute presentation with minimal notes and keep 90% of the audience engaged” is measurable. You can test it. You can improve it.

Create a simple tracking system. This could be as basic as a spreadsheet where you note what you practiced, what feedback you got, and what you’ll work on next. Or record yourself doing the skill monthly so you can compare how you were doing three months ago versus now. You’ll be surprised how much you’ve improved once you see it side by side.

When you’re assessing your progress, be honest about where you actually are. Overestimating your progress is tempting, but it’ll derail you. Accurate self-assessment lets you calibrate your practice to exactly where you need it.

Common Mistakes That Slow Down Your Progress

Even with all the right principles, people still get derailed. Usually by the same mistakes, over and over.

The biggest one? Confusing consumption with learning. You can watch 50 YouTube videos on a skill and still not be able to do the skill. Watching is passive. Doing is active. Spend way more time doing than consuming. Read the article, then immediately apply what you learned. Watch the video, then practice what you saw. The learning happens in the doing.

The second mistake is perfectionism. You’re waiting until you’re “ready” to share your work, get feedback, or move to the next level. Readiness is a myth. You get ready by doing. Share your work before it feels perfect. Get feedback on your rough draft. Try the harder challenge even though you might fail. That’s where the learning is.

The third mistake is underestimating how long real skill development takes. You’re not going to become genuinely skilled in a few weeks. Most people underestimate the time commitment by a factor of 5 or 10. That’s not a bummer—it just means you need to be in this for the long game. Consistency over months and years beats intensity over weeks.

Creating Your Actual Skill Development Plan

All of this is nice in theory, but here’s how you actually make it work in your life.

Start with one skill. Not five. One. Pick something that matters to you—something you actually want to be good at, not something you think you should learn.

Then answer these questions:

- What specifically am I trying to get better at? Not “communication.” Maybe “asking good questions in meetings” or “writing clear emails.” Specific.

- How will I practice this? What’s your deliberate practice going to look like? How often? For how long?

- How will I get feedback? Who’s going to tell you if you’re improving? A mentor? A community? Your manager?

- Where does this fit in my week? Habit stack it onto something you already do. Don’t create a new time block if you don’t have to.

- How will I measure progress? What does “better” actually look like? How will you know you’re improving?

Write these down. Literally write them down. The act of writing makes them more real and more likely to actually happen.

Then start. Not perfectly. Not when everything’s set up just right. Just start. Imperfect action beats perfect planning every single time.

FAQ

How long does it actually take to develop a real skill?

This varies wildly depending on the skill and your definition of “real skill.” But as a rough baseline, expect 100-300 hours of deliberate practice to reach intermediate competency in most skills. That’s not hours of passive learning—that’s focused, challenging practice where you’re pushing your limits. For complex skills like public speaking or writing, you might need 500+ hours to reach genuine expertise. The point is: it’s a commitment, but it’s a doable one if you’re consistent.

What if I don’t have a mentor for the skill I’m learning?

Mentors are amazing, but they’re not required. Communities can provide the feedback and accountability that mentors do. Online communities, cohort-based courses, accountability partners, or even peer feedback from others learning the same skill can fill that gap. The key is having someone other than yourself evaluating your progress.

How do I know if I’m practicing wrong?

You’re practicing wrong if you’re not getting feedback and you’re not adjusting based on that feedback. You’re practicing wrong if you’re doing the comfortable stuff instead of the hard stuff. You’re practicing wrong if you’re not tracking progress and you’re not seeing improvement. If any of those are true, change your approach. It’s not about working harder—it’s about working smarter.

Can I develop multiple skills at once?

Technically yes, but practically, most people shouldn’t. Your brain has limited bandwidth for deliberate practice. You’ll see better results focusing on one skill at a time, getting to a solid level of competency, and then moving on. If you absolutely need to work on multiple skills, make sure one is much more advanced than the other so they’re not competing for the same mental resources.

What if I’m not naturally talented at this skill?

Good news: natural talent matters way less than people think. Consistency, smart practice, and good feedback matter way more. Some people will have initial advantages, sure. But expertise comes from deliberate practice, not from being naturally gifted. This is actually liberating—it means that with the right approach, you can develop any skill you’re willing to work on.